I started this visualization to show how first-year classes at the highly rejective colleges had changed since COVID-19 forced them all to go to a test-optional approach for the Fall of 2021. But it sort of took on a life of its own after that, as big, beefy data sets often do.

The original point was to help discount the conventional wisdom, which is propped up by a limited, old study of a small set of colleges that showed test-optional policies didn’t affect diversity. I did this post last year, after just one year of data made it fairly clear they did at the institutions that had the luxury of selecting and shaping their class.

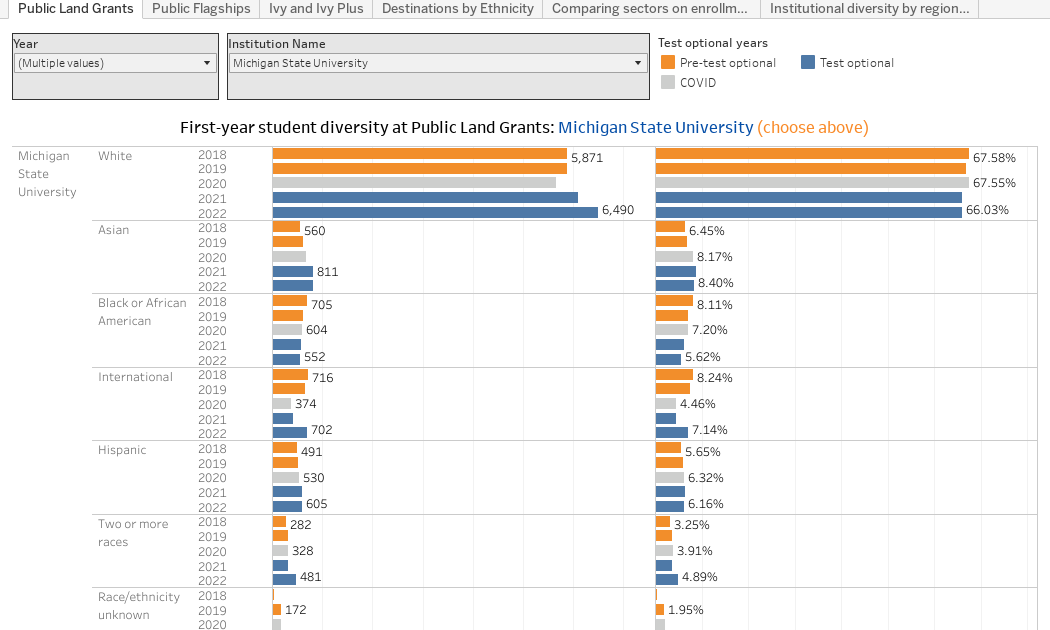

This year I took it a little farther. The views, using the tabs across the top, show the same trends (now going to 2022) for Public Land Grants, Public Flagships, the Ivy and Ivy+ Institutions. In each case, choose one using the control.

Note that I had colored the years by national trends: 2018 and 2019 are pre-test optional, gray is COVID, and blue is post-test optional. This is not to say that any individual college selected either required tests or went test-optional in those years, but rather shows the national trend. And remember these show enrolling students, not admitted students, which is why gray is critical; we know COVID changed a lot of plans, and thus 2020 may be an anomalous year.

The fourth view shows where students of any selected ethnicity enroll (again, use the dropdown box at the top to make a selection); the fifth view breaks out ethnicity by sector; and the final view allows you to look at diversity by sector and region (to avoid comparing diversity in Idaho, California, and Mississippi, for instance, three states with very different racial and ethnic makeups.)

On all views, hovering over a data point explains what you’re seeing.

If you work at a college or university, or for a private company that uses this data in your work, and want to support my time and effort, as well as software and web hosting costs, you can do that by buying me a coffee, here. Note that I won’t accept contributions from students, parents, or high school counselors, or from any company that wants to do business with my employer.

And, as always, let me know what jumps out at you here.