I still remember walking into my first Association of Media Practice Educators conference, sometime around the turn of the millennium.

I was a very junior academic, wide-eyed and slightly overwhelmed. Until that point, I’d assumed research lived only in books and journals.

My degree had trained me to write about creative work, not to make it.

That event was a revelation. Here were filmmakers, designers, artists, and teachers talking about the doing as research – not as illustration or reflection, but as knowledge in its own right. There was a sense of solidarity, even mischief, in the air. We were building something together: a new language for what universities could call research.

When AMPE eventually merged with MeCCSA – the Media, Communication and Cultural Studies Association – some of us worried that the fragile culture of practice would be swallowed by traditional academic habits. I remember standing in a crowded coffee queue at that first joint conference, wondering aloud whether practice would survive.

It did. But it’s taken twenty-five years to get here.

From justification to circulation

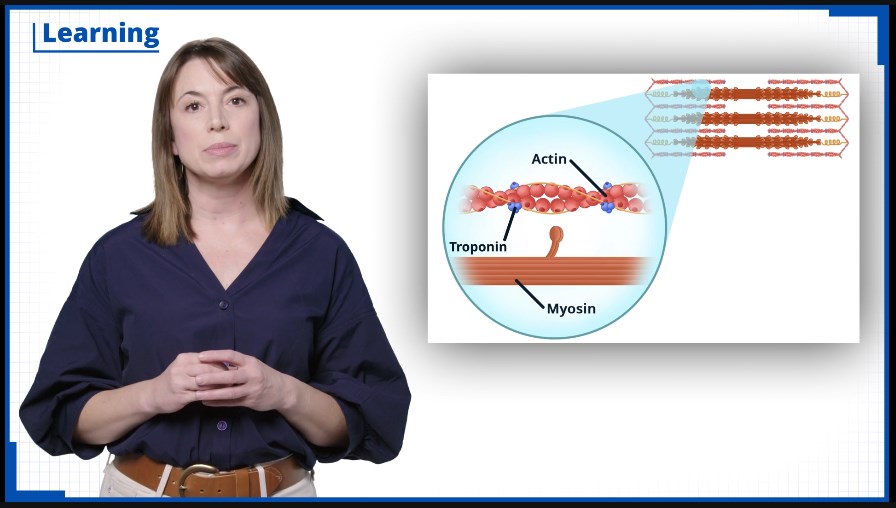

In the early days, the fight was about legitimacy. We were learning to write short contextual statements that translated installations, performances, and films into assessable outputs. The real gatekeeper was always the Research Excellence Framework. Creative practice researchers learned to speak REF – to evidence, contextualise, and theorise the mess of creative making.

Now that argument is largely won. REF 2021 explicitly recognised practice research. Most universities have templates, repositories, and internal mentors to support it. There are still a few sceptics muttering about rigour, but they’re the exception, not the rule.

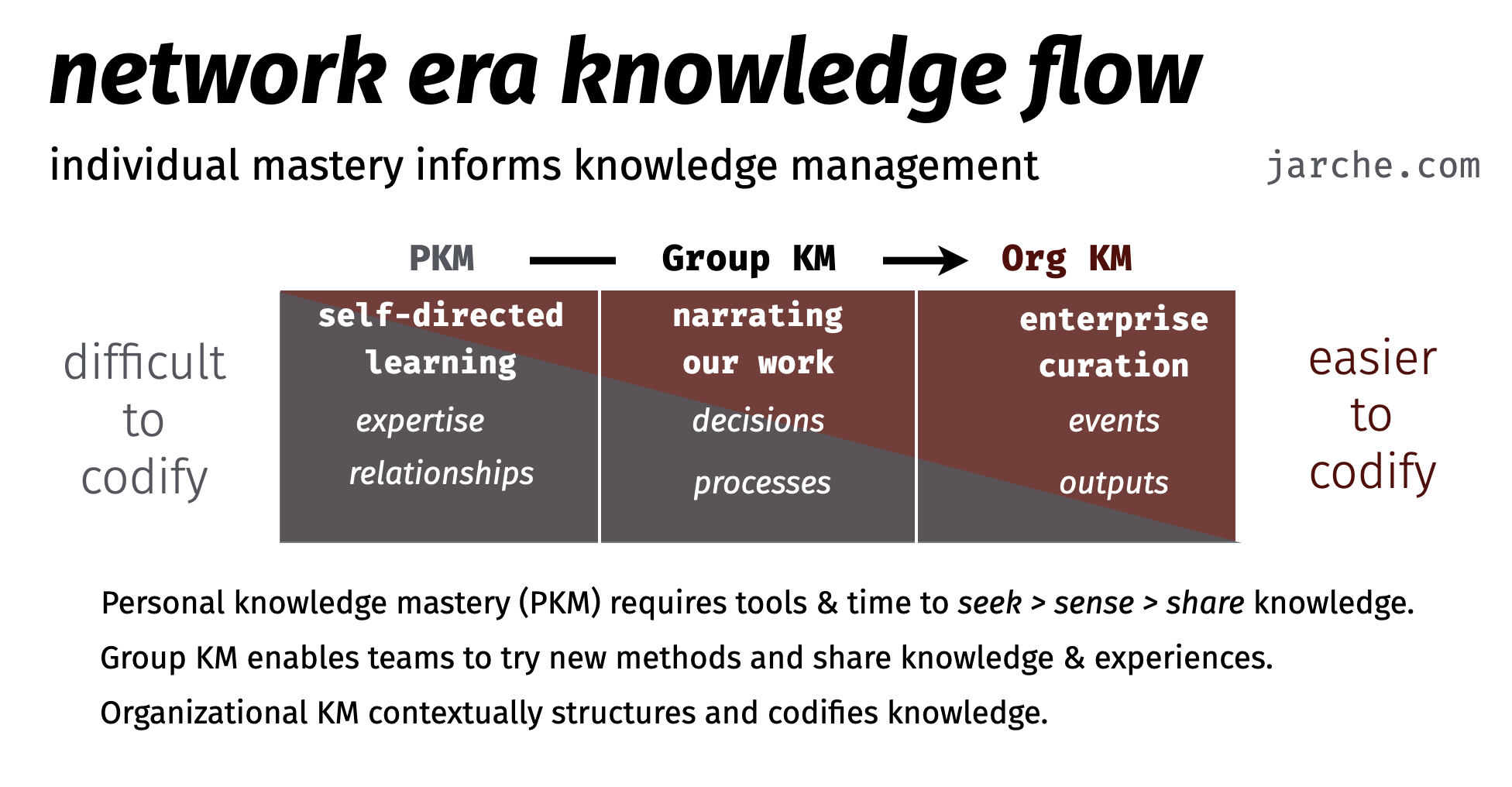

If creative practice makes knowledge, the challenge today is not justification. It’s circulation.

Creative practice is inherently cross-disciplinary. It doesn’t sit neatly in the subject silos that shape our academic infrastructure. Each university has built its own version of a practice research framework – its own forms, repositories, and metadata – but the systems don’t talk to one another. Knowledge that begins in the studio too often ends up locked inside an institutional database, invisible to the rest of the world.

A decade of blueprints

Over the past few years, a string of national projects has tried to fix that.

PRAG-UK, funded by Research England in 2021, mapped the field and called for a national repository, metadata standards, and a permanent advisory body. It was an ambitious vision that recognised practice research as mature and ready to stand alongside other forms of knowledge production.

Next came Practice Research Voices and SPARKLE in 2023 – both AHRC-funded, both community-driven. PR Voices, led by the University of Westminster, tested a prototype repository built on the Cayuse platform. It introduced the idea of the practice research portfolio – a living collection that links artefacts, documentation, and narrative. SPARKLE, based at Leeds with the British Library and EDINA, developed a technical roadmap for a national infrastructure, outlining how such a system might actually work.

And now we have ENACT – the Practice Research Data Service, funded through UKRI’s Digital Research Infrastructure programme and again led by Westminster. ENACT’s job is to turn all those reports into something real: a national, interoperable, open data service that makes creative research findable, accessible, and reusable. For the first time, practice research is being treated as part of the UK’s research infrastructure, not a quirky sideshow to it.

A glimpse of community

In June 2025, Manchester Metropolitan University hosted The Future of Practice Research. For once, everyone was in the same room – the PRAG-UK authors, the SPARKLE developers, the ENACT team, funders, librarians, and plenty of curious researchers. We swapped notes, compared schemas, and argued cheerfully about persistent identifiers.

It felt significant – a moment of coherence after years of fragmentation. For a day, it felt like we might actually build a network that could connect all these efforts.

A few weeks later, I found myself giving a talk for Loughborough University’s Capturing Creativity webinar series. Preparing for that presentation meant gathering up a decade of my own work on creative practice research – the workshops I’ve designed, the projects I’ve evaluated, the writing I’ve done to help colleagues articulate their practice as research. In pulling all that together, I realised how cyclical this story is.

Back at that first AMPE conference, we were building a community from scratch. Today, we’re trying to build one again – only this time across digital platforms, data standards, and research infrastructure.

The policy challenge

If you work in research management, this is your problem too. Practice research now sits comfortably inside the REF, but not inside the systems that sustain the rest of academia. We have no shared metadata standards, no persistent identifiers for creative outputs, and no national repository.

Every university has built its own mini-ecosystem. None of them connect.

The sector needs collective leadership – from UKRI, the AHRC, Jisc, and Universities UK – to treat creative practice research as shared infrastructure. That means long-term funding, coordination across institutions, and skills investment for researchers, librarians, and digital curators.

Without that, we’ll keep reinventing the same wheel in different corners of the country.

Coming full circle

Pulling together that presentation for Capturing Creativity reminded me how far we’ve come – and how much remains undone. We no longer need to justify creative practice as research. But we still need to build the systems, the culture, and the networks that let it circulate.

Because practice research isn’t just another output type. It’s the imagination of the academy made visible.

And if the academy can’t imagine an infrastructure worthy of its own imagination, then we really haven’t learned much from the last twenty-five years.