When the NHS launched its Long-Term Workforce Plan in 2023, it set out an ambitious vision: to nearly double the number of doctors and nurses through the first fully comprehensive national workforce strategy in its history. For universities (the institutions responsible for training these professionals) it offered rare clarity. Yet without a clear funding and implementation framework, progress quickly stalled.

Two years on, that ambition has not only faltered but, in some respects, reversed. Both universities and NHS trusts face severe financial pressures: universities are cutting courses and staff, while trusts reduce job vacancies and apprenticeships. Meanwhile, universities remain excluded from decisions shaping the future workforce.

Although Labour supported the Conservatives’ plan while in opposition, in office it has taken a different approach. The NHS 10-year plan, published last June, gave limited attention to workforce issues.

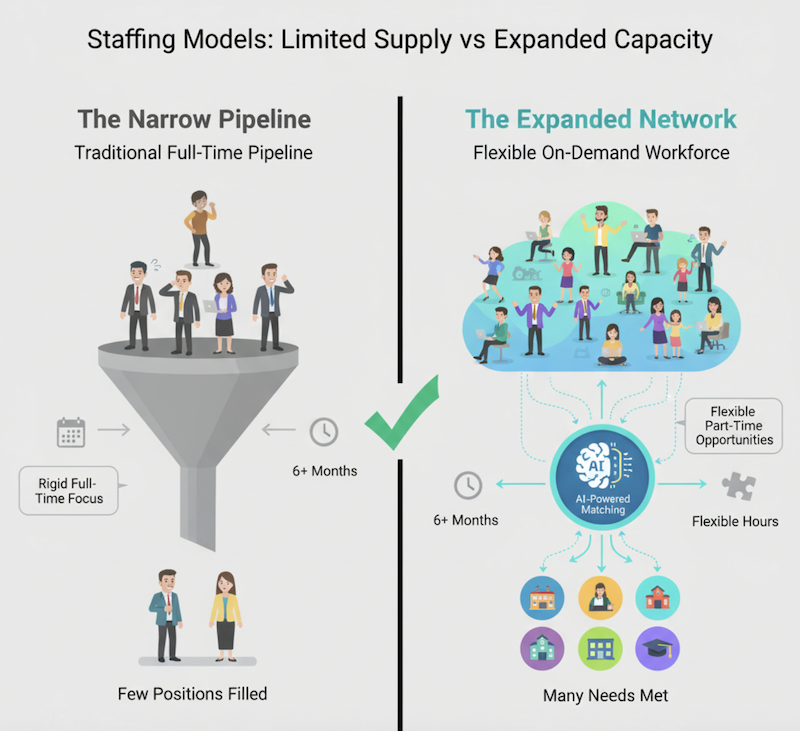

With the government committed to reducing net migration, boosting homegrown staff remains a priority, though now on a smaller scale. An entirely new workforce plan is expected in the spring, envisaging fewer staff – but with better conditions and “more exciting roles”. In the meantime, a radical change in the relationship between the NHS and higher education is needed.

Contradictions

Alliance universities educate a third of England’s nurses, a significant share of allied health professionals, and a growing number of doctors. We’re innovating and collaborating on degree apprenticeships, opening medical schools and creating new pathways into health careers. Yet as with the previous long-term workforce plan, universities have barely been consulted – despite being central to delivering the workforce the NHS needs.” The recent call for evidence on the forthcoming plan didn’t mention universities once.

That is why key bodies representing healthcare educators recently sent a joint letter to health ministers calling for education, training, and research to be at the heart of the 10-year workforce plan. We are asking for a cross-government taskforce to coordinate efforts on student recruitment, retention, clinical placement capacity, and planning. These systematic issues are at the heart of the NHS workforce crisis – not poor-quality education and training.

Universities can help scale solutions, but only if government stops pulling policy levers in opposite directions. These contradictions undermine progress: the Department for Education’s decision to scrap level 7 apprenticeship funding directly conflicts with the NHS’ emphasis on advanced practice. Add to that the patchy engagement of Integrated Care Systems with educators, leaving universities uncertain about their role in local workforce planning.

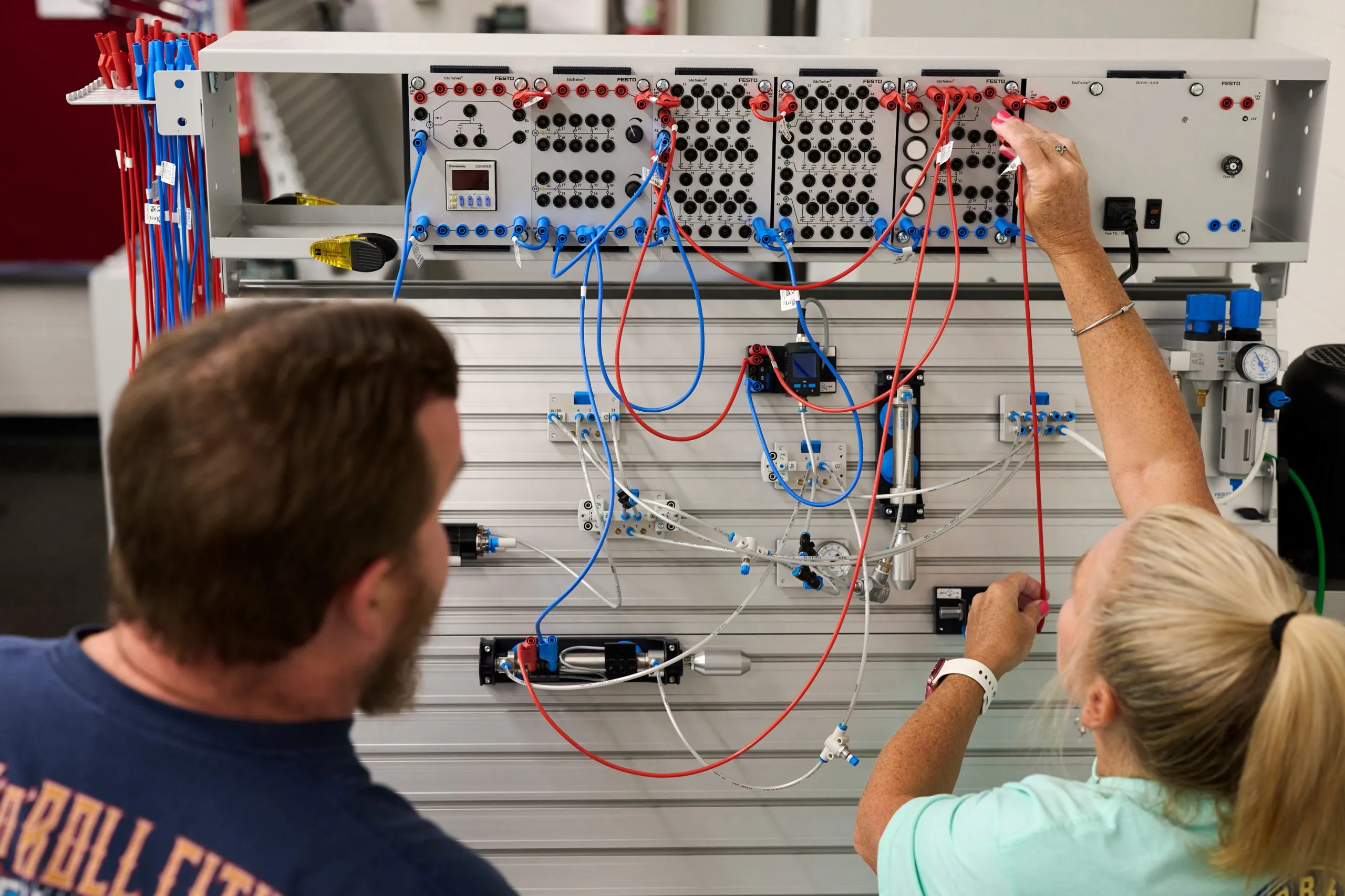

Despite these mixed signals, universities continue to devise innovative approaches. At Oxford Brookes, the School of Nursing and Midwifery operates as a joint venture with two NHS trusts, sharing leadership and strategic planning to align education with workforce needs. In North Central London, Middlesex University works with the Integrated Care Board to raise the profile of nursing in social care, providing bespoke training that has cut A&E admissions from care homes. These partnerships show what’s possible when universities are treated as equal partners, aligning education with workforce needs and improving patient outcomes.

Joint work on the pipeline

But innovation alone can’t compensate for a shrinking recruitment pipeline, which is still largely unaddressed by policymakers. Nursing applications have fallen post-Covid and in the wake of the cost-of-living crisis. Attrition figures often mislead: many students do not drop out but delay completion due to life pressures – financial strain, caring responsibilities, and mental health challenges. Intensive placements leave little room for paid work, compounding these pressures. University Alliance supports the RCN’s proposal for a loan forgiveness scheme in exchange for time served and an uprated learning support fund to keep students in training.

If we want a future-ready nursing and midwifery workforce, we need to ditch the outdated obsession with counting hours and start focusing on outcomes. The NMC will soon be consulting to reduce its requirements from 4,600 to 3,600 programme hours, which is a small step in the right direction.

The pandemic showed what’s possible when regulators embrace flexibility. Emergency standards unlocked innovation in simulation and digital training. Today, Alliance universities use augmented reality mannequins and advanced simulation suites to replicate hospital and home-care settings – boosting confidence and easing placement pressures. Scaling these solutions, however, requires capital investment and regulatory reform – neither of which is happening fast enough.

Flexibility isn’t just about training hours – it’s about pathways too. Degree apprenticeships have been one of the NHS’s success stories, creating alternative routes into nursing and allied health professions. However, without attention, the NHS risks losing one of its most flexible entry points into the profession.

Social Market Foundation research found that intensive inspection regimes, audits and reporting processes from multiple oversight bodies are driving up costs and leading to some universities leaving the market. Some successful programmes have been paused because employers can’t afford backfill costs. Anglia Ruskin University developed the UK’s first medical doctor degree apprenticeship to tackle shortages in rural communities at considerable cost – only for the level 7 funding decision to slam the brakes on expansion.

Long-term ambitions

Finally, if the NHS is to move beyond a hospital-centric model – a long-term government ambition – universities must help drive that change. The infrastructure to support the shift to community care has been hollowed out over decades.

Alliance universities are piloting community nursing pathways, increasingly arranging placements in primary care and social care settings. But growth is significantly hampered by a shortage of community staff able to supervise students. Without investment and clear career routes, graduates will continue to gravitate toward acute settings, and the vision of neighbourhood care will remain a mirage.

The next workforce plan is a chance to break the cycle of short-term fixes and build a sustainable system. That means joining-up health and education policy, embracing regulatory flexibility, and investing in the infrastructure that enables transformation. Above all, it means treating universities as strategic partners. Without these measures, ambitions for a homegrown, future-ready workforce will remain out of reach.