On a grey March morning in 2008, a ministerial stand-in cut the ribbon on a £25 million glass and steel building that was supposed to transform Southend-on-Sea.

Then chief executive of the Higher Education Funding Council for England (HEFCE), David Eastwood had been hastily switched in as guest-of-honour to replace then-minister Bill Rammell.

At the funding council, Eastwood had overseen the flow of millions in public money into this seaside town sixty miles east of London. Behind him was the University of Essex’s Gateway Building – six floors of lecture theatres, seminar rooms and local ambition.

The name had been suggested by Julian Abel, a local resident, chosen because it captured both the building’s location in the Thames Gateway regeneration zone and its promise as “a gateway to learning, business and ultimate success.”

Colin Riordan, the university’s vice chancellor, captured the spirit of the moment:

While new buildings are essential to this project, what we are about is changing people’s lives.

Local dignitaries toured the building’s three academic departments – the East 15 Acting School, the School of Entrepreneurship and Business, and the Department of Health and Human Sciences.

They admired the Business Incubation Centre designed to nurture local start-ups. They inspected the GP surgery and the state-of-the-art dental clinic where supervised students from Barts and The London would provide free treatment to locals – already 1,000 patients in just eight weeks.

This wasn’t just a university building. It was the physical manifestation of New Labour’s last great higher education experiment – the idea that you could transform left-behind places by planting universities in them – fixing “cold spots” and “left-behind places” with warm words and big buildings. It was as much economic infrastructure as it was education infrastructure.

Once, Southend had been “a magnet for day trippers”, then a shabby seaside resort, then a town so deprived that it attracted EU funding. Into that landscape dropped a £26.2 million glass box with “amazing views of the Thames Estuary on one side and a derelict Prudential block on the other,” explicitly aiming to revive the town’s flagging economy.

Riordan said the campus would “restore the physical fabric of the town centre” and act as a “magnet” for outsiders, while Eastwood supplied a line about a university being “global, national and local” at the same time – world-class research, national recruitment, local benefit.

Initially, Southend grew beyond the Gateway. East 15 got Clifftown Studios in a converted church, giving the town a theatre and performance space. The Forum – a joint public/university/college library and cultural hub – opened in 2013 as a flagship partnership between Southend Council, Essex and South Essex College, widely lauded as an innovative three-way civic project. For a while, Southend genuinely felt like a university town – at least in the city-centre streets around Elmer Approach.

But now seventeen years later, the University of Essex has announced it will close the Southend campus. The Gateway Building will be emptied, 400 jobs will go, and the town’s dream of becoming “a vibrant university town” may now end with recriminations about financial sustainability and falling international student numbers.

The council leader, Daniel Cowan, says:

…our city remains perfectly placed to play a major national role in higher education, business, and culture.”

But does it?

To understand how Southend’s university dream died, we need to understand how it was born – in the marshlands of Thames Gateway, in the policy papers of Whitehall, and in the peculiar optimism of Britain in the mid-2000s, when anything seemed possible if you just built it.

In the dying days of the John Major years, to the east of London was a mess – dominated by derelict wharves, refineries and marshland – but it was also a potential route for the new Channel Tunnel Rail Link. In 1991, Michael Heseltine told MPs that the new line “could serve as an important catalyst for plans for the regeneration of that corridor” and announced a government-commissioned study into its potential.

The thinking was formalised in 1995, when ministers published the Thames Gateway Planning Framework (RPG9a) – regional planning guidance for a “major regional growth area” extending from Newham and Greenwich in London to Thurrock in Essex and Swale in Kent. It was very much late-Conservative spatial policy – trying to capture South East housing and employment growth in a defined corridor while using new infrastructure and land-use policy to civilise what one background paper called the “largest regeneration opportunity in Western Europe.”

New Labour scaled the whole thing up. In February 2003, John Prescott launched a Sustainable Communities Plan, which “set out a vision for housing and community development over the next 30 years”, with the Thames Gateway as its flagship growth area. Southend became the seaside town that would anchor the estuary’s eastern edge, absorb some of the new housing, and symbolise that this wasn’t just about London’s fringe – but about reviving places that had been left behind by deindustrialisation.

2001’s Thames Gateway South Essex vision even identified Southend’s future role as the cultural and intellectual hub and a “higher education centre of excellence for South Essex.”

In a 2006 Commons adjournment debate on “Southend (Regeneration)”, David Amess stitched the university and college expansions into promises of 13,000 new jobs and thousands of homes by 2021. Accommodating growth at the University of Essex Southend campus and South East Essex College, he argued, was key to turning the town centre into a “cultural hub”, alongside plans for a public and university library and performance and media centre.

By the time John Denham published A New University Challenge: Unlocking Britain’s Talent in March 2008, Southend was the exemplar. In the South Essex case study the prospectus tells a neat story – Essex’s involvement began in 2001 via validated programmes at South East Essex College, evolved into a “distinctive” partnership pulling a research-intensive university into a major widening participation and regeneration project.

With support from HEFCE, central and local government, it aimed to grow student numbers in the town from 700 to 2,000 by 2013 as “the beginning of a vision to make Southend a vibrant university town.”

There were plenty more. In “A New University Challenge,” Denham reminded readers that, since 2003, capital funding and additional student numbers had already gone into eleven areas – Barnsley, Cornwall, Cumbria, Darlington, Folkestone, Hastings, Medway, Oldham, Peterborough, Southend and Suffolk – with HEFCE agreeing support for six more – Blackburn, Blackpool, Burnley, Everton, Grimsby, and North and South Devon.

He estimated that around £100 million in capital had been committed so far, with capacity for some 9,000 students when all the projects were fully functioning.

Cornwall was another showcase. The Penryn (then Tremough) campus – developed through the Combined Universities in Cornwall scheme – used EU Objective One money and UK government funding via the South West RDA to build a shared site for Falmouth and Exeter in a county with historically low higher education participation and a fragile, seasonal economy.

Subsequent evidence to Parliament from Cornwall Council was explicit that CUC was designed to deliver economic regeneration as much as access, focusing European investment on “business-facing activity” and experimentation in outreach to firms that had never worked with universities before.

Cumbria got its own mini-origin story. Denham described the new University of Cumbria – launched in 2007 – as “a new kind of institution” with distributed campuses in urban and rural settings – designed to meet diverse learner needs and provide, with partners, the “skills that are essential” to create the workforce that would go on to decommission the Sellafield nuclear power plant.

Later DIUS reporting, REF environment statements and parliamentary evidence on the nuclear workforce all reprise the same themes – Cumbria as an anchor institution, a regional skills engine and a piece of the civil nuclear skills jigsaw.

Suffolk was presented as the archetypal “cold spot.” In 2005 UEA and Essex, backed by Suffolk County Council, Ipswich Borough Council, EEDA and the Learning and Skills Council, secured £15 million from HEFCE to create University Campus Suffolk on Ipswich Waterfront – a county of over half a million people with no university, low participation and significant planned growth.

Denham sold UCS as both a response to education under-supply and an enabler of economic regeneration. Later coverage in The Independent made the same point in more colourful language – Ipswich finally had its own glamorous waterfront campus “full of thousands of students.”

Barnsley, Oldham, Darlington and the like were framed more modestly – university centres in FE colleges that extended HE access to people “who might not otherwise consider participating in higher education.” In Barnsley’s case that meant a town-centre site opened in 2005 by Huddersfield, with investment from HEFCE, Yorkshire Forward and Objective 1 funds, later taken over by Barnsley College but still offering Huddersfield-validated degrees and hosting around 1,600 HE students.

Folkestone, Hastings and Medway were presented as coastal or post-industrial variations on the theme – attempts to use university presence in under-served towns as a driver of creative-quarter regeneration, skills upgrading and image change. University Centre Folkestone, a Canterbury Christ Church/Greenwich joint venture, showed up in coastal regeneration reports as a way to tackle deprivation through improved skills and productivity in South Kent.

The Universities at Medway partnership between Kent, Greenwich, Canterbury Christ Church and Mid-Kent College was talked up in SEEDA case studies as a £50 million dockyard campus replacing thousands of lost shipbuilding jobs and housing over 10,000 students.

All of that was then plugged into the macro-economy story. Denham leaned on work suggesting that a one percentage point increase in the graduate share of the workforce raised productivity by around 0.5 per cent, and argued that higher education contributes over £50 billion a year to the UK economy, supporting 600,000 jobs.

The logic was pretty simple – if you want a more productive, knowledge-intensive economy, you need more graduates in more places – and not just in the big cities.

In March 2008 Denham called the scattered activity the “first wave” – and then announced a competition for the next one:

We believe we need a new ‘university challenge’ to bring the benefits of local higher education provision to bear across the country.

He got his headlines. He asked HEFCE to consult not just institutions but also RDAs, local authorities, business and community groups on how to identify locations and shape proposals. The goals were twofold – “unlocking the potential of towns and people” and “driving economic regeneration.”

HEFCE’s Strategic Development Fund was given £150 million for the 2008–11 spending review. Denham suggested that over six years the fund could support up to twenty more centres or campuses, with commitments in place by 2014 and roughly 10,000 additional student places once mature.

The criteria for bids were revealing about the politics of the moment. Proposals had to demonstrate that they would widen participation, particularly among adults with level 3 who had never considered HE. They had to slot into local economic strategies – supplying high-level skills, supporting business start-ups and innovation, anchoring graduates who might otherwise leave. And they had to show strong HE/FE collaboration, buy-in from councils and RDAs, credible demand modelling, and the ability to manage complex multi-funded capital projects.

HEFCE dutifully ran a two-stage process – statements of intent followed by full business cases. By late 2009, after sifting twenty-three initial bids, the funding council concluded that six were strong enough to develop further, subject to the next spending review. Those six were Somerset (with Bournemouth University), Crawley (Brighton), Milton Keynes (Bedfordshire), Swindon (UWE), Thurrock (Essex) and the Wirral (Chester).

But the initiative wasn’t to last. The 2010 election brought a coalition government that scrapped RDAs, squeezed capital budgets and shifted the English HE settlement onto nine-thousand-ish fees and income-contingent loans. HEFCE’s Strategic Development Fund withered. “Alternative providers” became the policy fashion – and the idea of a central pot funding twenty shiny new public campuses was in the past.

The promised headline – twenty new campuses, twenty new “university towns” – never happened. Instead we got a patchwork of university centres, joint ventures and re-badged FE HE hubs, while national rhetoric shifted from “unlocking towns and people” to “competition and choice.”

If we look back now at the original seventeen, we find four basic trajectories.

Barnsley and Oldham have settled into the HE-in-FE pattern. University Campus Barnsley, opened in 2005 by Huddersfield with HEFCE, Yorkshire Forward and Objective 1 support, transferred to Barnsley College in 2013 and now runs as the college’s HE arm, with Huddersfield still validating degrees. University Campus Oldham followed a similar route – opened in 2005 under Huddersfield’s banner and managed by Oldham College since 2012, delivering Huddersfield-validated awards alongside its own.

Cornwall and Medway look closer to what Denham imagined. The Penryn campus now hosts around 6,000 students on a shared Falmouth–Exeter site, with Objective One and SWRDA funding widely credited as crucial to its development.

Universities at Medway, established in 2004 at Chatham Maritime, has struggled – Canterbury Christ Church has all but pulled out, Kent’s numbers are small. The glossy case studies boasting of its £300 million boost to the local economy and its role in remaking a dockyard area that lost 7,000 jobs overnight look less glossy in 2025 – and now, of course, Kent and Greenwich are merging.

Cumbria and Suffolk were the two that ended up as fully fledged universities. The University of Cumbria, established in 2007 from a merger of colleges and satellite campuses, describes itself in REF and internal strategy documents as an “anchor institute” created to catalyse regional prosperity and pride, while continuing to play a role in the nuclear skills ecosystem around Sellafield. University Campus Suffolk secured university title and degree-awarding powers in 2016, with official narrative and sector commentary stressing its success in “transforming the provision of higher education in Suffolk and beyond” – although a significant proportion of its students are franchised.

Grimsby, Blackburn, Blackpool, Burnley, and the Devon centres fall into the “quietly important” category. The £20 million University Centre Grimsby opened in 2011 and now offers a large suite of higher-level programmes in partnership with Hull and through the TEC Partnership’s own degree-awarding powers. Grimsby Institute marketing describes it as a “dedicated home” for HE and one of England’s largest college-based providers. Similar stories play out in Blackburn, Blackpool and Petroc/South Devon – college-based university centres that rarely appear in the national HE debate but matter enormously for local progression and skills.

Folkestone and Hastings show us the fragility of hanging regeneration hopes on small coastal campuses. University Centre Folkestone operated from 2007 to 2013 as a Canterbury Christ Church/Greenwich initiative, featuring in coastal regeneration studies as a way to address deprivation and skills deficits and energise the creative quarter. But by the early 2010s it had wound down its HE offer, with the buildings folded into Folkestone’s broader cultural infrastructure.

Hastings saw an original centre replaced in 2009–10 by the University of Brighton in Hastings as the university’s fifth campus – itself the subject of fierce local protest when Brighton decided in 2016 to close the site and move provision into a partnership “university centre” model with Sussex Coast College.

Peterborough was a late-blooming outlier. The original University Centre Peterborough, developed with Anglia Ruskin, is now joined by ARU Peterborough – a campus opened in 2022 with significant “levelling up” funding and endlessly described by ministers as addressing a higher education cold spot and boosting local productivity. It was, in many ways, Denham’s model revived under a different party label – but few like it are left.

As for the “Universities Challenge” push, in Somerset, Bridgwater & Taunton College developed University Centre Somerset, offering degrees validated by HE partners. In Crawley, what had been imagined as a bid for a campus manifested as higher-level technical and university-level provision in Crawley College and the Sussex & Surrey Institute of Technology.

Milton Keynes’ ambitions funnelled into University Centre/Campus Milton Keynes, now part of the University of Bedfordshire, with periodic political chatter about eventually having a fully fledged MK university. On the Wirral, Wirral Met’s University Centre at Hamilton Campus offers degrees accredited by Chester, Liverpool and UCLan as part of a broader skills and regeneration role. Thurrock saw South Essex College expand its University Centre presence – exactly the sort of FE-based HE model Denham said he wanted.

Elsewhere, Chester has pulled out of Telford. Gloucestershire is winding down Cheltenham. The University College of Football Business (UCFB) no longer operates in Burnley. Man Met sold Crewe to Buckingham. USW is no longer in Newport, UWTSD is closing Lampeter, Durham is out of Stockton, and Cumbria has mothballed Ambleside.

It turns out that on that grey March morning in 2008, David Eastwood was right. To sustain a full-fledged university campus – with all of the spill out benefits often envisaged – you need international students, national recruitment of home students and local students. Immigration policy change has made the first harder. A lack of deliberate student distribution has made the second harder. And closures like Southend’s leave local students like this.

I personally chose Southend due to being a single parent, wanting to build my career in nursing whilst getting that extra time with my little girl.

In its “National Conversation on Immigration” in 2018, citizens’ panels for British Future saw real benefits of international students – it called for student migration and university expansion to be used “to boost regional and local growth in under-performing areas,” and for any major expansion of student numbers to be government-led with the explicit aim of spreading the benefits more widely, including via regional quotas on post-study work visas and new institutions in cold spots.

It talked of “a new wave of university building” and said institutions should be located in places that have experienced economic decline, have fewer skilled local jobs, or are social mobility “cold spots” – with criteria including distance from existing universities and socio-economic need. They then give a worked list of ten suggested locations – Barnstaple, Berwick-upon-Tweed, Chesterfield, Derry-Londonderry, Doncaster, Grimsby, Shrewsbury, Southend and Wigan.

But as we’ve covered before, immigration policy – both during expansion and contraction – is almost always place-blind.

The Resolution Foundation’s Ending stagnation A New Economic Strategy for Britain makes a similar point – it rejects making existing campuses ever larger, and instead calls for new ones able to serve cold-spots “like Blackpool and Hartlepool.” It cites evidence that increasing the number of universities in a region – a 10 per cent rise – is associated with around a 0.4 per cent increase in GDP per capita.

This Tony Blair Institute paper from 2012 – surely the inspiration for Starmer’s 66 per cent target speech – calls for new universities in “left-behind regions” as a way to reduce spatial disparities and break intergenerational disadvantage. Chris Whitty’s 2021 report that highlighted the “overlooked” issues in coastal towns suggested shifting medical training to campuses in deprived towns.

And at a Policy Exchange event on the fringe of Conservative Party Conference that year, Michael “Minister for Levelling Up” Gove was asked about the potential for new universities to bring economic benefits to “places like Doncaster and Thanet.” Gove simply said: “I agree.”

The current Labour government’s Post-16 education and skills white paper makes familiar noises about addressing “cold spots in under-served regions.” But there’s no money for new campuses, no Strategic Development Fund, no New University Challenge. Instead, there’s a working group. And around the edges, we’re watching the geographical distribution of higher education shrink.

Without deliberate planning, sustained funding and political will, clustering will continue to cluster. Universities will consolidate in cities where mobile students want to study and where critical mass already exists. The cold spots will get colder.

OfS talks of universities needing “bold and transformative action.” It doesn’t mean transforming places – it means surviving financially. Even mergers save little money unless they lead to campus closures. And campus closures mean communities losing not just current educational provision but future possibility – the chance that their children might stay local and still get a degree, that their town might attract the businesses and cultural institutions that follow universities, that they might be something more than a void on the educational map.

The Robbins expansion of the 1960s worked because it created entire new institutions with sustained funding and genuine autonomy. The polytechnic expansion of the 1970s worked because it built on existing technical colleges with deep local roots. The conversion of polytechnics to universities in 1992 worked because it recognised existing success rather than trying to create it from nothing. But most attempts since to plant universities in cold spots through satellite campuses and partnership arrangements have struggled – because the system stubbornly refuses to pull levers based on place.

Once a university exits stage left, the impacts can be devastating. Despite promises that the merger and rebranding of the university into the University of South Wales in 2013 would not reduce campuses or student numbers, the 32-acre campus in Newport was closed in 2016 – when a largeish slice of arts and media courses moved to the Cardiff Atrium campus.

Student numbers in the city collapsed from around 10,000 in 2010/11 to just 2,600 a decade later – a drop that left the city, in the words of one local councillor, as “a poor man’s Pontypridd” when it comes to higher education.

The campus had been the city’s third highest employer – now the economic contribution of higher education to the local economy has all but evaporated. As one local put it:

There’s a lot of hate for students until they’re gone.

The Southend closure announcement came with promises too. The university would “support students through the transition.” The local council would “explore options for the site.” The MP would “fight for the community.”

Some will point the finger at the university. But we would be very foolish indeed to blame universities for shutting down campuses that they can’t sustain in a market-led model.

Doing so obscures the fundamental question – if universities are as crucial to regional development as everyone claims, why do we leave their geographical distribution to market forces? Why do we build campuses with regeneration money then expect them to survive on student fees? Why are we place-specific with our physical capital but place-blind with our human capital? Why do we keep repeating the same mistakes?

The answer is uncomfortable – because we’ve never really believed in geographical equity in higher education. We’ve played at it, thrown money at it during boom times, made speeches about it. But when times get hard, when choices must be made, the cold spots are always first to lose out.

The 1960s planners who chose Canterbury over Ashford and Colchester over Chelmsford understood that university location was too important to leave to chance. They made deliberate choices about where to invest for the long term. They understood that some places would need permanent subsidy to sustain provision, and they accepted that as the price of geographical equity.

We’ve lost that understanding. We’ve replaced planning with market mechanisms, strategy with initiatives, and long-term thinking with political cycles. Places like Southend are the ones that will pay the price – and sadly, it won’t be the last.

Many high school seniors are now focusing on what they will do once they graduate – or how they don’t at all know what is to come.

Families trying to guide and support these students at the juncture of a major life transition likely also feel nervous about the open-ended possibilities, from starting at a standard four-year college to not attending college at all.

I am a mental health counselor and psychology professor.

Here are four tips to help make deciding what comes after high school a little easier for everyone involved:

I have worked with many college students who are interested in a particular career path, but are not familiar with the job’s day-to-day workings.

A parent, teacher or another adult in this student’s life could connect them with someone they shadow at work, even for a day, so the student can better understand what the job entails.

High school students may also find that interviewing someone who works in a particular field is another helpful way to narrow down career path options, or finalize their college decisions.

Research published in 2025 shows that high school students who complete an internship are better able to decide whether certain careers are a good fit for them.

Full-time students can pay anywhere from about US$4,000 for in-state tuition at a public state school per semester to just shy of $50,000 per semester at a private college or university. The average annual cost of tuition alone at a public college or university in 2025 is $10,340, while the average cost of a private school is $39,307.

Tuition continues to rise, though the rate of growth has slowed in the past few years.

About 56% of 2024 college graduates had taken out loans to pay for college.

Concerns about affording college often come up with clients who are deciding on whether or not to get a degree. Research has shown that financial stress and debt load are leading to an increase in students dropping out of college.

It can be helpful for some students to look at tuition costs and project what their monthly student loan payments would be like after graduation, given the expected salary range in particular careers. Financial planning could also help students consider the benefits and drawbacks of public, private, community colleges or vocational schools.

Even with planning, there is no guarantee that students will be able to get a job in their desired field, or quickly earn what they hope to make. No matter how prepared students might be, they should recognize that there are still factors outside their control.

I have found that some students feel they should go to a four-year college right after they graduate because it is what their families expect. Some students and parents see a four-year college as more prestigious than a two-year program, and believe it is more valuable in terms of long-term career growth.

That isn’t the right fit for everyone, though.

Enrollment at trade-focused schools increased almost 20% from the spring of 2020 through 2025, and now comprises 19.4% of public two-year college enrollment.

Going to a trade school or seeking a two-year associate’s degree can put students on a direct path to get a job in a technical area, such as becoming a registered nurse or electrician.

But there are also reasons for students to think carefully about trade schools.

In some cases, trade schools are for-profit institutions and have been subjected to federal investigation for wrongdoing. Some of these schools have been fined and forced to close.

Still, it is important for students to consider which path is personally best for them.

Research has shown that job satisfaction has a positive impact on mental health, and having a longer history with a career field leads to higher levels of job satisfaction.

One strategy that high school graduates have used in recent years is taking a year off between high school and college in order to better determine what is the right fit for a student. Approximately 2% to 3% of high school graduates take a gap year – typically before going on to enroll in college.

Some young people may travel during a gap year, volunteer, or get a job in their hometown.

Whatever the reason students take gap years, I have seen that the time off can be beneficial in certain situations. Taking a year off before starting college has also been shown to lead to better academic performance in college.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Join HEPI for a webinar on Thursday 11 December 2025 from 10am to 11am to discuss how universities can strengthen the student voice in governance to mark the launch of our upcoming report, Rethinking the Student Voice. Sign up now to hear our speakers explore the key questions.

This blog was kindly authored by Utkarsh Leo, Lecturer in Law, University of Lancashire (@UtkarshLeo)

UK law students are increasingly relying on AI for learning and completing assessments. Is this reliance enhancing legal competence or eroding it? If it is the latter, what can be done to ensure graduates remain competent?

Studying law equips students with key transferable skills – such as evidence-based research, problem solving, critical thinking and effective communication. Traditionally, students cultivate doctrinal (and procedural) knowledge by attending lectures, workshops and going through assigned academic readings. Thereafter, they learn how to apply legal principles to varying facts through assessments and extracurriculars like moot courts and client advocacy. In this process, they learn how to construct persuasive arguments and articulate ideas, both orally and in writing. However, with widely available and accessible Gen AI, students are taking shortcuts in this learning process.

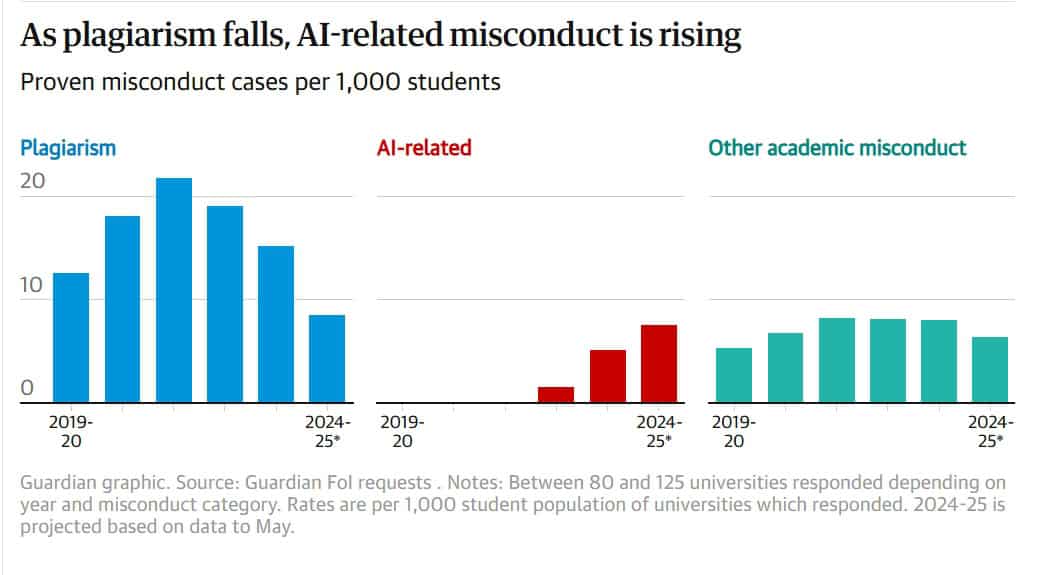

The HEPI/Kortext Student Generative AI Survey 2025 looked into AI use by students from a range of subjects. It paints a grim picture: 58% of students are using AI to explain concepts and 48% are using it to summarise articles. More importantly, 88% are using it for assessment related purposes – a 66% increase compared to 2024.

Student Generative AI Survey 2025, Higher Education Policy Institute

Students are relying on shortcuts largely due to rising economic inequality. Survey data published by the National Union of Students shows 62% of full-time students work part-time to survive. This translates into reduced studying time, limited participation in class discussions and extracurriculars. Understandably, such students may find academic readings (which are often complex and voluminous) as a chore, further reducing motivation and engagement. In this context, AI offers a quick fix!

Prompt and output generated by perplexity.ai on 7 November 2025 showing AI-produced case summaries.

Quick fixes, as shown above, promote overreliance: resulting in cognitive replacement. Most LLB first-year programmes aim to cultivate critical legal thinking: from the ability to apply the law and solve problems in a legal context to interpreting legislative intent to reading/finding case law and developing the skills to spot issues, weigh precedents and constructing legal arguments. Research from neuroscience shows that such essential skills are acquired through repeated effort and practice. Permitting AI usage for learning purposes at this formative stage (when students learn basic law modules) inhibits their ability to think through legal problems independently – especially in the background of the student cost-of-living crisis.

More importantly, only 9 out of more than 100 universities require law degree applicants to sit the national admission test for law (LNAT) – which assesses reasoning and analytical abilities. This variability means we cannot assume that all non-LNAT takers possess the cognitive tools necessary for legal thinking. This uncertainty reinforces the need to disallow AI use in first-year law programmes to ensure students either gain or hone the necessary skills to do well in law school.

Furthermore, from a technical perspective, the shortcomings of AI summaries are well known. AI models often merge various viewpoints to create a seemingly coherent answer. Therefore, a student relying on AI to generate case summaries enhances the likelihood of detaching them from judicial reasoning (for example, the various structural/substantive principles of interpretation employed by judges). It risks producing ill-equipped lawyers who may erode the integrity of legal processes (a similar argument applies to statutes).

Alongside this, AI systems are unreliable: from generating fake case-law citations to suggesting ‘users to add glue to make cheese stick to pizza.’ Large language models (LLMs) use statistical calculation to predict the next word in a sequence – therefore, they end up hallucinating. Despite retrieval-augmented generation – a technique for enhancing accuracy by enabling LLMs to check web sources – the output generated can be incorrect if there is conflicting information. Furthermore, without thoughtful use, there is an additional concern that AI sycophancy will further validate existing biases. Hence, despite the AI frenzy, first year students will be better off if they prioritise learning through traditional primary and secondary sources.

Certainly, we cannot prohibit student’s from using AI in a private setting; but we can mitigate the problem of overreliance by designing authentic assessments evaluated exclusively through in-person exams/presentations. This is more likely to encourage deeper engagement with the module. Now more than ever, this is critical. Despite rising concerns of AI misuse and the inaccuracy of AI text detection primarily due to text perplexity (high false positives; especially for students for whom English is not their first language), core law modules (like contract law and criminal law) continue to be assessed through coursework (for either 50% or more of the total module mark).

However, sole reliance on in-person exams will not suffice! To promote deeper module engagement (and decent course pass rates), the volume of assessments will need to be reduced. As students are likely to continue working to support themselves, universities could benefit from the support and cooperation of professional bodies and the Office for Students. In fact, in 2023, the Quality Assurance Agency highlighted that universities must explore innovative ways of reducing the volume of assessments, by ‘developing a range of authentic assessments in which students are asked to use and apply their knowledge and competencies in real-life’.

To promote experiential learning, one potential solution could be to offer assessment exemption based on moot-court participation. Variables such as moot profile (whether national/international), quality of memorial submitted, ex-post brief presentation on core arguments, and student preparation could be factored to offer grades. Admittedly, not all students will pursue this option; however, those who choose to participate will be incentivised.

Similarly, summer internships or law clinic experiences can be evaluated through patchwork assessment where students can complete formative patches of work on client interviews, case summaries and letters before action, followed by a reflective stitching piece highlighting real world learning and growth.

It is crucial to emphasise that despite the critique of Gen AI, its vast potential to enhance productivity cannot be overlooked. Nevertheless, what merits attention is that such productivity is contingent on thoughtful engagement and basic domain specific knowledge – which is less likely to be found in first year law students.

Thus, a better approach is to delay approved use of AI until the second year of law. To ensure graduates are job ready, modules such as Alternative Dispute Resolution and Professional Skills could go beyond prompting techniques to include meaningful engagement with technology: through domain specific AI tools, contract review platforms and data-driven legal analytics ‘to support legal strategy, case assessment, and outcomes’.

Above all, despite advances in tech, law will remain a people-centred profession requiring effective communication skills. Therefore, in the current climate, law school education should emphasise oral communication skills. Prima facie, this approach may seem disadvantageous to students with special needs, but it can still work with targeted adjustments.

In sum, universities have a moral responsibility to churn out competent law graduates. Therefore, they must realistically review the abilities of AI to ensure the credibility of degrees and avoid mass-producing surface-level lawyers.

Acknowledgement: I am grateful to Rachel Nir, Director of EDI at the School of Law and Policing, University of Lancashire, for her insightful comments and for kindly granting the time allowance that made this research possible.

In the summer of 2025, the CLOP hacking group—operating from Russia—exploited weaknesses at the University of Phoenix, exposing sensitive data on thousands of students and staff. The breach was devastating, yet Russia was not officially condemned as an adversary.

The contrast with U.S. policy toward countries like Venezuela is striking. Venezuela faces crippling sanctions, economic isolation, and constant political pressure under the banner of protecting democracy and human rights. Meanwhile, Russian-based cybercriminals are allowed to inflict real harm on U.S. institutions with little official pushback. The reason, officials say, is a lack of direct evidence tying these attacks to the Russian state. But the discrepancy reveals a deeper hypocrisy: punitive measures are applied selectively, often based on geopolitical convenience rather than consistent principles.

CLOP-style attacks exploit vulnerabilities in U.S. institutions. Universities, especially those operating on outdated IT systems and under private equity pressures, are frequent targets. Students—many already burdened by debt and systemic inequities—bear the brunt when personal data is exposed. Yet the broader conversation rarely extends to foreign actors who take advantage of these weaknesses or to the structural failures within U.S. education.

Venezuela’s citizens suffer sanctions and economic hardship, while Russian cybercriminals operate from the safety of a country that tolerates them, so long as domestic interests remain untouched. This double standard undermines the credibility of U.S. claims to principled leadership and exposes the uneven moral framework guiding foreign policy.

Higher education becomes a battleground in this selective application of power. Cyberattacks, fraud, and systemic negligence converge to threaten students and faculty, revealing the real victims of international hypocrisy. Protecting U.S. institutions requires acknowledging both the foreign actors who exploit weaknesses and the domestic policies and practices that leave them vulnerable.

The CLOP breach is more than a single incident—it is a reflection of a system that punishes some nations for internal crises while tolerating damage inflicted by others on critical domestic infrastructure. Until U.S. policy addresses both sides of this equation, the cost will continue to fall on the most vulnerable: the students, staff, and faculty caught in the crossfire.

Sources: U.S. Department of Education reports; investigative journalism on CLOP and Russian cybercrime; analyses of U.S.-Venezuela sanctions and policy.

The U.S. Department of Education recently released a draft proposal of regulatory language that outlines how short-term programs could become — and remain — eligible for the newly created Workforce Pell Grants.

The Workforce Pell program will allow students in programs as short as eight weeks to receive Pell Grants. It was created as part of the massive spending and tax package that Republicans passed this summer and takes effect in July 2026.

The Education Department released the draft proposal ahead of negotiations next week to hash out the regulatory language governing how the program will operate.

In a process known as negotiated rulemaking, stakeholders representing different groups affected by the regulations are to meet Monday to begin discussing the policy details of the Workforce Pell program. Participants include students, employers and college officials.

If they reach consensus on regulatory language, the Education Department will have to use that when formally proposing regulations for Workforce Pell. If the stakeholders don’t reach consensus, the agency will be free to write its own regulations.

The draft proposal outlines the steps state officials will have to take for workforce programs to begin qualifying for Workforce Pell Grants and what student outcome metrics they would need to hit to remain eligible for the grants.

The massive budget bill expands Pell Grants to certain workforce-training programs lasting between eight to 15 weeks. For programs to be eligible, governors must consult with state boards to determine if they prepare students to enroll in a related certificate or degree program, meet employers’ hiring needs, and provide training for high-skill, high-wage or in-demand occupations, among other requirements.

Under the Education Department’s draft proposal, each state’s governor would work with its workforce development board to establish which occupations are considered high-skill, high-wage or in-demand and publicly share how the state made those determinations. Governors would also have to seek feedback from employers to develop a written policy for determining whether programs meet local hiring needs.

As established in the spending bill, short-term programs must then receive approval from the Education Department’s secretary before they can qualify for Workforce Pell. Under the statute, programs have to exist for at least one year before they can get approval.

The Education Department’s proposal adds that the secretary wouldn’t be able to approve a program until “one year after the Governor determines that the program met all applicable requirements.”

This means that “all programs would need to wait an additional year before becoming eligible, even if they had already existed for more than a year,” according to a Thursday analysis of the draft from James Hermes, associate vice president of government relations at the American Association of Community Colleges.

AACC plans to work with negotiators to push for that provision to be changed, Hermes said.

Under the Education Department’s draft language, programs would need to maintain a job placement rate of 70% to remain eligible during the first two years of the Workforce Pell program. But after the 2027-28 award year, they would need 70% of their graduates to specifically land jobs in fields for which they’re being trained, according to the proposal.

During each award year for Workforce Pell, the statute bars programs from posting tuition and fee prices that are higher than the “value-added” earnings of their students. It calculates that difference by subtracting 150% of the federal poverty line from the median earnings of students who completed their program three years prior.

To make that calculation, the Education Department proposed first checking whether that cohort contains at least 50 students. If not, it would look back up to two more years to see if the program meets that benchmark. If the program still misses that threshold, it will look back one more year to achieve a cohort of 30 students.

If looking back those additional years doesn’t yield data from at least 30 students, the Education Department would not complete the “value-added” calculation, according to the draft. However, the agency’s proposal doesn’t address how that would impact a program’s eligibility for Workforce Pell.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

The committee that advises on national vaccine policy today overturned a decades-long recommendation that newborns be immunized for hepatitis B, a policy credited with nearly eliminating the highly contagious and dangerous virus in infants.

The decision came in an 8-3 vote from the committee that has been handpicked by Health and Human Service Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr., a long-time vaccine skeptic. It followed three previous failed attempts to vote on the measure and two days of contentious, confused hearings that further undermined the group’s credibility.

Amy Middleman, a longtime committee liaison and a University of Oklahoma pediatrics professor, said it was the first time the committee “is voting on a policy that, based on all of the available and credible evidence … actually puts children in this country at higher risk — rather than lower risk — of disease and death.”

Susan J. Kressly, the president of the American Academy of Pediatrics, which is continuing to recommend the hepatitis B vaccine at birth, called the committee’s guidance “irresponsible and purposely misleading” and said that it will bring about more infections in infants and children.

“This is the result of a deliberate strategy to sow fear and distrust among families” she said.

The members of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, known as ACIP, who voted in favor of the new guidance said the universal birth dose, first introduced in 1991, had likely played a small role in the reduction of acute cases and noted that the country’s policy was an outlier when compared to those of peer nations, which have more targeted approaches. They also raised concerns about the safety of the vaccine, arguing there were insufficient trials done, a claim that has been widely debunked.

The committee’s new recommendations still include a dose of the vaccine within the first 24 hours of life for infants born to hepatitis B-positive mothers. But for those born to mothers testing negative, they recommend “individual-based decision-making, in consultation with a health care provider” to decide “when or if” to give the vaccine.

Removing the universal birth dose “has a great potential to cause harm,” dissenting committee member Joseph Hibbeln said, “and I simply hope that the committee will accept its responsibility when this harm is caused.”

The committee also voted to upend the rest of the schedule for the hepatitis B vaccine, which is required for school attendance in the vast majority of states and historically included three doses in an infant’s first year. Now, after the first dose, parents will be encouraged to ask their doctors to check infants for a sufficient immune response before proceeding with any future doses, a practice that currently lacks any scientific evidence, according to vaccine experts.

The recommendation now heads to Jim O’Neill, the acting head of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, newly installed after September’s ousting of the previously confirmed director, who said she resisted Kennedy Jr.’s demands to pre-approve vaccine recommendations and fire career scientists.

O’Neill’s decision could impact not only the vaccine’s availability, but also its accessibility, since both public and private health insurers look to these policies to determine coverage.

“The American people have benefited from the committee’s well-informed, rigorous discussion about the appropriateness of a vaccination in the first few hours of life,” O’Neill said in a statement Friday.

Former CDC director Rochelle Walensky, now a Harvard University medical professor who recently co-authored a paper on the importance of the hepatitis B birth dose, projected that eliminating it for infants whose mothers test negative will raise the number of newborn hepatitis B cases by 8% each year.

“We rely on an infrastructure of vaccines not only to protect ourselves and our children, but to protect our communities and one another,” Walensky said. “Today’s meeting was just another one of those chisels in the infrastructure.”

Paul Offit, the director of the Vaccine Education Center and an attending physician in the Division of Infectious Diseases at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, referred to the committee as “a clown show” in an interview on CNN Friday morning.

“Honestly, it’s a parody of what this committee used to be,” he said. “It’s hard to watch, and for those of us who care about children, it’s especially hard to watch.”

Offit said he doubted that the committee understood how hepatitis B was transmitted in young children — half the time through the mother during childbirth but just as often through casual contact with someone who was chronically infected and didn’t know it. About 50% of the millions of Americans infected with hepatitis B are unaware of it.

“By loosening the [immunization] reins, you are just putting children in harm’s way,” Offit said.

The hepatitis B vaccine was first recommended by ACIP in 1982. Before that point, an estimated 200,000 to 300,000 people, including about 20,000 children, were infected with the highly contagious virus each year.

This was particularly dangerous for infants who have a 90% chance of developing liver cancer or chronic liver disease, if they contract the virus. For 4- and 5-year-olds, that chance remains high at 30-40%.

Committee members argued the guidance change reflected a return to pre-1990s policies that focused on a targeted approach, rather than a universal one. A number of them said that these earlier practices were successful and sufficient in cutting hepatitis B rates, a claim other experts — including those at the CDC — refuted.

In a departure from typical practices, presentations on disease rates and safety concerns at the hearing were not given by CDC subject-matter experts, but instead were led by a climate researcher and a known anti-vaccine activist, who authored a since-retracted paper on the impact of rising autism rates.

When one CDC hepatitis B expert was invited to weigh in during a question-and-answer period, he expressed concern about the presented research and emphasized the lack of evidence to support the committee’s changes. Middleman jumped in at one point to correct the committee when it misinterpreted “the conclusions of my own study.”

Throughout the meeting, Kennedy Jr.’s appointees spoke about the importance of protecting parents’ rights, seemingly pitting this against public health policy.

“My personal bias is to err on the side of enabling individual decision making and individual rights over the right [of] the collective,” said Robert Malone, the committee’s vice chair who led the meeting since newly appointed chair Kirk Milhoan, a cardiologist and critic of the COVID vaccine for children, was unavailable to attend in person.

Earlier this year, the committee also voted to change policies surrounding the measles, mumps, rubella and varicella (chickenpox) combination vaccine and this year’s COVID 19 booster.

Historically, committee members were highly qualified medical professionals, vetted for months to years before serving. But, in an unprecedented upheaval in June, Kennedy Jr. fired all 17 existing advisory members via a Wall Street Journal op-ed — after promising he would leave the committee’s recommendations intact — and hastily replaced them.

Many of the new members have espoused anti-vaccine rhetoric and other scientific misinformation and a number of them do not have medical degrees or significant experience in the field.

Cody Meissner, a professor at Dartmouth’s Geisel School of Medicine and the only committee member to have previously served, also opposed the guidance change.

“We’ve heard ‘do no harm’ is a moral imperative,” he said. “We are doing harm by changing this wording, and I vote no.”

The committee vote was the latest in a wave of policy changes, firings and general chaos at the CDC and HHS that have alarmed experts since Kennedy Jr. took charge almost a year ago.

Last week, the Food and Drug Administration’s chief medical and scientific officer released an unsupported memo claiming COVID-19 vaccinations had contributed to the deaths of at least 10 children. Last month, Kennedy Jr. ordered CDC staff to change information on their website to promote a link between vaccines and autism, a widely discredited theory that he has promoted for years.

According to Offit, the negative impacts are already being seen: This year tallied the greatest number of measles cases (1,828) since it was declared eliminated in 2000, the majority of which were in unvaccinated children, two of whom died. It marked the first pediatric measles deaths since 2003.

There have also been nearly 300 childhood flu deaths — among predominantly unvaccinated kids — the most seen since the country’s last flu pandemic and whooping cough cases are surging in some states. The highly contagious respiratory infection, prevented through the DTaP vaccine, has killed three unvaccinated infants in Kentucky.

Did you use this article in your work?

We’d love to hear how The 74’s reporting is helping educators, researchers, and policymakers. Tell us how

Federal lawmakers are divided over whether the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act and the Protection of Pupil Rights Amendment should be used to protect student’s LGBTQ+ status from parents or to reveal it.

The disagreements arose during a Wednesday hearing held by the House Education and Workforce’s Early Childhood, Elementary and Secondary Education subcommittee as the two originally bipartisan laws — which are meant to protect students’ records and information collection from unauthorized disclosures — are increasingly being wielded by federal authorities to crack down on districts over their privacy policies on issues like students’ gender pronouns.

“This should not be a partisan issue,” said Rep. Kevin Kiley, R-Calif., chairman of the subcommittee. “Keeping parents in the dark is wrong.”

Kiley and witnesses at the hearing said some school districts keep dummy files in order to keep parents in the dark about information like a preferred name a student is using in school, have “secret transition policies” directing staff to withhold from parents if children express a gender identity different from their sex at birth, and conduct “intrusive” surveys and evaluations of students’ mental health.

However, representatives and witnesses on the other side of the issue say that policies requiring parents to know students’ gender identities, sexual orientations, or pronoun and name changes jeopardize student safety and housing security in some cases, and also violate student rights.

“Forcing teachers to out every student every time they want to go by a different name or engage in some form of self-expression is an unrealistic expectation and disrupts the teacher-student bond,” said Rep. Suzanne Bonamici, D-Ore. “If students are not talking to their parents about their gender identity, maybe there’s a good reason for that. A lot of homeless youth are LGBTQ, and they get kicked out of their house when they reveal their gender identity.”

LGBTQ+ people are overrepresented in the homeless youth population, according to the National Network for Youth, a nonprofit that aims to reduce youth homelessness. These youth are 120% more likely to experience homelessness than their non-LGBTQ+ peers and represent up to 40% of all youth experiencing homelessness, despite accounting for only 9.5% of the overall population.

Administration cracks down on schools protecting LGBTQ+ students

According to Parents Defending Education, a conservative parental rights group, over 1,200 districts impacting more than 21,000 schools and a collective 12.4 million students have policies stating that district personnel “can or should keep a student’s transgender status hidden from parents.”

Nearly half of those noted districts are in California, which has a state law that went into effect this year preventing school employees from disclosing any information related to a student’s sexual orientation, gender identity, or gender expression to any other person without their consent. The law also prohibits schools from requiring employees to disclose such information to parents and is the subject of an Office for Civil Rights investigation launched in March.

By contrast, at least 15 states have policies requiring schools to reveal students’ LGBTQ+ status under some circumstances, according to the Movement Advancement Project, which tracks issues related to transgender students.

The hearing last week and disagreements over the essence of the privacy laws — as well as LGBTQ+ student safety — came as the Trump administration increasingly uses FERPA and PPRA to investigate schools for civil rights violations, similar to the investigation in California.

In August, for example, it launched investigations into four Kansas school districts for alleged FERPA violations also related to withholding student information from parents’ related to LGBTQ+ status. “My offices will vigorously investigate these matters to ensure these practices come to an end,” said McMahon in a statement related to the Kansas investigations.

Ultimately, these investigations could be used to withhold funds from schools, many of which are in states with LGBTQ+ protection laws requiring such school policies.

In March, the U.S. Department of Education sent districts a Dear Colleague letter warning that documents such as gender plans being withheld from educational records available to parents may be considered civil right violations.

“Many states and school districts have enacted policies that imply students need protection from their parents,” said U.S. Education Secretary Linda McMahon in a March statement. “Going forward, the correct application of FERPA will be to empower all parents to protect their children from the radical ideologies that have taken over many schools.”

Last week, the issue also made it to the 2nd U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals after a mother said a New York school violated her constitutional rights when it didn’t inform her of the child’s request that staff use gender neutral pronouns and a masculine name. The mother in Vitsaxaki v. Skaneateles Central School District ultimately withdrew the student from the district. Alliance Defending Freedom is representing the mother.

At least three other cases filed by ADF are also pending, including against Texas’ Houston Independent School District and Michigan’s Rockford Public Schools.

The issue of privacy laws and its new enforcement strategy under the Trump administration also made it to lawmakers’ radar as the Education Department is downsizing by transferring the management of many of its core oversight responsibilities, including for elementary and secondary education, to other agencies.

Such a move would weaken the enforcement of privacy laws, some witnesses and lawmakers said.

In 2018, the Education Department’s Office of the Inspector General said the department failed to conduct timely and effective investigations of complaints related to data privacy, as cases piled up in a backlog without any effective strategy to track the number or status of the complaints it received.

“And that has largely not been resolved,” said Cody Venzke, senior policy counsel at the ACLU’s National Political Advocacy Department, during the House subcommittee hearing. Dissolving the department could compromise student privacy oversight and make the backlog worse, he said.

“Moreover, FERPA and the PPRA — they are premised on receiving funds from the department of education,” said Venzke. “If those critical grants are dispersed elsewhere throughout the federal government, FERPA and PPRA become worth no more than the paper they’re printed on.”

Online programs are no longer a nice-to-have. They are essential, with many schools looking to online as their primary growth lever amid market headwinds. A strong portfolio of online programs can allow institutions to grow enrollment, reach new student populations, and future-proof their offerings. But building, launching, and sustaining a successful online program operation requires a certain expertise that many internal teams lack. And even if your team has the right skills, you have to ask, “Do they really have the capacity to take on one more thing?”

Given that time and budget are often finite, and the deep digital expertise needed to launch, scale, and sustain competitive online programs, its easy to see why traditional Online Program Management (OPM) providers would seem like a turn-key solution. At first glance, this revenue-share OPM model appears checks all the boxes: no upfront cost, faster time to market, and a larger team to shoulder the workload. It makes sense why the model feels appealing.

But there is no easy button in higher ed. When something appears to be too good to be true on the surface, chances are high that it is. What seems like a low-risk solution today can turn into a strategic liability tomorrow. Beneath the surface of many revenue-share OPM agreements are hidden costs, inflexible contracts, and a loss of institutional control that only becomes clear once you’re locked in.

We’ve had more than a few partners come to us waving the white flag. They’re stuck in contracts that overpromised and continue to under deliver. But with little-to-no insight into the daily operations, data, and marketing strategy, it becomes increasingly difficult to find a way out that doesn’t jeopardize what’s already in motion or stall the programs still in planning. Said plainly, this is not the symbiotic relationship they were sold.

And more and more institutions are catching on. Since 2021, new revenue-share deals have declined by nearly 50% as colleges and universities opt for fee-for-service agreements that offer transparency, flexibility, and allows schools to retain long-term control. A fee-for-service partnership puts both the school and its strategic partner in the front seat to work together to get to the final destination (the driver) and best way to get there (the navigator). And in some cases, these partnerships can be a stop gap, ensuring what is in motion stays in motion while schools work to build their own internal OPM, eventually being able manage its online programs autonomously.

The punchline is you have options. “OPM” is not synonymous with revenue-share. Enablement-based partners (like Collegis Education) now deliver the same services without taking over your strategy or forcing you to relinquish control.

The challenges with traditional OPM contracts aren’t always obvious upfront. It’s only after the ink dries that many institutions realize the trade-offs run deeper than expected — disrupting operations and long-term strategy. As more institutions reconsider their approach to online growth, it’s essential to understand what’s really at stake.

So before you lock your school into an OPM’s golden handcuffs and sign a revenue-share agreement, here’s what you need to know.

There is a big difference between external support and ceding control entirely. The traditional OPM model assumes ownership of key functions like marketing and enrollment, resourcing decisions, and budget allocation. That’s not collaboration; it’s surrendering some of your biggest strategic levers to an outside vendor whose priorities are often centered on enrollment volume, not institutional mission. And once you’ve given up that control, getting it back is not easy.

The traditional OPM pitch (no upfront fees and no budget approvals) sounds like a win. But many institutions end up giving away 50–80% of tuition revenue for up to a decade or more. That’s funding that could be reinvested in faculty, student support, or academic innovation. Without that revenue, it becomes even harder to build internal teams or expand capabilities, leaving you stuck with the same constraints that pushed you toward an OPM in the first place. It’s a cycle that’s tough to break.

And because these contracts often lack transparency, the full financial impact isn’t clear until it’s too late. Every year in a revenue-share agreement can mean more value slipping through your fingers.

Even after giving up a significant share of tuition revenue, many institutions report underwhelming enrollment growth, unclear ROI, and limited visibility into performance. Add to that the cultural disconnects between OPM teams and on-campus leadership (different priorities, processes, and communication styles) and frustration can quickly mount.

When that much is at stake, institutions deserve meaningful outcomes, aligned strategies, and a partner that’s fully invested in their success.

OPM agreements are intentionally rigid and extremely difficult to exit. The OPM wants to increase your dependency on them and often includes tail clauses, auto-renewals, and other provisions that make it challenging to walk away. Even if the partnership underperforms, you may still be stuck paying for services you no longer want or need while the market moves on without you.

With revenue-share models, the tech stack is owned by the OPM and often lives outside your ecosystem. That means your access and visibility is limited to what the OPM is willing to share. This lack of transparency into performance data slows decision-making and leaves you dependent on tools you don’t control or fully understand. For a modern institution, that dependency is downright dangerous.

Download our “Building an Internal OPM” workbook for practical steps to assess your internal capabilities and create a sustainable, in-house online program strategy.

Revenue-share OPMs are financially incentivized to prioritize enrollment growth over educational outcomes. That often results in generic courses, diluted rigor, and aggressive marketing — especially toward vulnerable student populations. One high-profile partnership between a university and its OPM provider made headlines when tuition was set high, outcomes lagged, and questions emerged about who was truly being served.

And because the OPM is essentially invisible to students, your institution bears the full weight of any backlash — whether it’s from prospective students, faculty, or the public. The long-term impact? Lower student satisfaction, reduced faculty trust, and reputational damage that’s hard to repair.

The Department of Education and several states are scrutinizing tuition-share deals. If regulations change or compliance gaps emerge, your institution will bear the legal and financial consequences. Unlike your vendor, you can’t opt out of oversight — your name, your accreditation, and your funding are all on the line.

Speaking of brand integrity, when traditional OPM vendors control your messaging, your communications, and your marketing funnel, your voice starts to disappear. The student experience and institutional identity can quickly diminish and become disjointed. What’s left is often little more than your logo on a landing page, detached from the values and mission that set your institution apart.

Revenue-share OPMs aren’t structured to make independence easy. Even if you’ve built internal capabilities over time, you may not have access to the data, systems, or strategic insight needed to take control. Without a clear runway to transition, institutions often feel forced to renew, because picking up the ball and running with it isn’t possible when you can’t see the full playbook.

Enablement-based, fee-for-service models let you control the pace, scope, and strategy. You keep your data, you own your student experience, and you build sustainable capacity to grow on your terms.

If your goal is to build a mission-aligned, financially sustainable online portfolio, outsourcing core capabilities may not be the answer. Traditional OPM models once helped institutions enter the online space, but today, they’re more likely to hold you back.

Don’t give away your tuition dollars. Don’t give up your data. And don’t sign away your flexibility.

Build smarter. Own your growth.

Let’s explore what a fee-for-service partnership could look like for your institution.

Higher ed is evolving — don’t get left behind. Explore how Collegis can help your institution thrive.