My go-to metaphor about travelling abroad is that initial comfort involves finding things that look similar that we understand, even if they’re a little different.

“Look mom, they call a Twix a Raider”, that kind of thing.

As such, a late night stop in a convenience store in Ottawa with Wonkhe’s own Debbie McVitty was a particular highlight of a week mooching Canadian higher education.

Do people in North America eat half of their huge bags of crisps at a time, or munch them all in one go? What is their reaction when they see our tiny tiny bags? Why are Walkers called Lay’s? Why does Hershey’s chocolate taste like those chemical cakes in urinals? Why can’t we buy a Curly Wurly?

It’s enormous fun, but you don’t learn much. On our study tours we always warn against settling for surface level observations – not just because “student representation” or a “course” might not refer to what we think they do, but also because it’s the systems, culture and assumptions that underpin what’s on the surface that really matter.

It’s why I’ve always found the sensation of going to sector conferences so unsatisfying. Folks from university A or sector B will tell you how they fixed issue A, or what they did to address issue B, and blurb often pretends that the examples will be actionable to help you justify the cost of going.

But it’s like getting someone to bring you back a bag of Cheezies. You can taste one and decide whether you like them – but you’ve no idea how many they eat, how often they eat them, how they became popular, why they’re still on sale, or whether their alarming bright Orange color is really a huge health risk.

Without that context, trying to regularly replicate the experience back home is impossible. And it’s why HESA’s Re:University event has been so enriching.

Billed as a kind of “innovation sandbox” for Canadian universities focused on how to adjust to the sector’s fiscal crisis, the big question has been – nobody wants to pay for the system we have built, so how can universities rethink their models?

And that’s a set of questions that demands both lateral thinking and depth thinking, and interrogating the examples you’re presented with.

Speedboat mode

Take “leadership”. One fascinating theme running through the event has been the extent to which leaders feel able to drive change – partly to respond to what students want, partly to deliver better value to the taxpayer, and partly to survive.

But in a culture where Senates and academic staff hold more power than we might find in the UK, there’s been a surface level sense that some of the more innovative models for curriculum, or credit, or “problem based learning” on offer from around the world would be impossible to implement.

I’ve therefore had all sorts of fun. On Day One, I was describing some of the models we’ve seen in Europe – which some surmised was down to their funding, or their government, or their regulation, or their “culture”, or the “power” that their managers must have.

Maybe. But given that Rectors (and often most of their management teams) are routinely elected by staff and students across Europe, that regulation in Canada is noticeably light touch (if present at all), and that they almost all cope on lower (high) staff-student ratios and units of resource than in Canada, something else must be going on.

One of my running theories is that in Europe rectors are elected mainly via their political skills, and then learn the relevant management skills on the job – which means they can often “carry” the “faculty” (staff) through change. By contrast in North America (and the UK), university leaders are selected on management skills and competencies, and then have to learn political skills – and some are found wanting.

That’s fine, at worst a little dull, when the funding and wider external environment is stable. But when the cruise ship needs to turn into a speedboat to avoid crashing into the iceberg, the source selection method becomes instructive.

And crucially, I’ve never met a student or staff representative who wants their university to go under. But I have met countless student and staff representatives who feel they’re often lied to, or held at arm’s length, or feel comfortable in simplistic resistance because they’ve never been positioned as partners in power.

And anyway, if it’s democracy that’s the problem, how have systems that often include large proportions or students and staff with voting power – including systems where students can exercise a veto – managed to reform to look more innovative over things like problem-based learning, or interdisciplinary, or experiential learning, than Canada and the UK?

I expect that one of the things that gets undervalued when people look at endless committees, or associations, or decision making bodies is that service causes us to consider others – other students, other departments, other universities, or other people.

There are obviously a lot of upsides to that if two thirds, or half of your students play a role like that at some stage as we see in some European countries – both for decision making, and for wider society.

Wheelbarrow diplomacy

Money matters, of course – the sense that the sector is underfunded is an almost universal issue around Global HE right now, and it’s been a key issue here in Ottawa.

In the opening session, former Ontario premier Dalton McGuinty reflected on the time in the 00s when he’d pushed through record investment in the sector:

In K to 12, with their substantial increase in funding, I got higher test scores and higher graduation rates and just a much stronger sense of satisfaction on the part of parents and taxpayers generally. In healthcare, I got lower wait times for MRI, CTs, cataracts, cancer care, cardiac, hips, knees, emergency department. I got measurable improvements that demonstrated that we were on the move and making significant measurable reforms. But in higher ed, I didn’t get the kind of reforms that I hoped for, that I can turn to a demanding public.

He added an amusing anecdote:

I used to joke that when I gave money to my universities, the metaphor we use was that they would say, all right, you’ve got a wheelbarrow full of money. Just drop it on that side of the moat and step back 100 paces, somebody’s gonna grab the goddamn wheelbarrow. Just get the hell out of here.

John Stackhouse, the senior VP in the Office of the CEO of the Royal Bank Canada, observed:

This is the guy who did that $6 billion for the sector, and 20 years later, feels he didn’t get quite the ROI, didn’t get the reform that he was looking for. That should be concerning to everyone here.

If you’re still in Twix and Raider mode, it’s often comforting to assume that what we have to communicate better – point out just how valuable/cool/important we are, and then they’ll re-open the wallet.

But Bob Rae, who was Premier of Ontario from 2003 to 2013 and is now Canada’s Ambassador and Permanent Representative to the United Nations, wasn’t so sure – recalling a moment when he’d been asked to help restructure the Toronto Symphony Orchestra:

The orchestra was great. It’s just that nobody was coming… I was in a meeting with the union, and we were waiting for the guy to come up from the States who was the head of the union, and he called me earlier to say, Don’t you dare impose any changes on this institution, because if you do it’ll affect every single orchestra in North America, and you can’t do it.

He resolved to speak to the members of the orchestra:

I went in and I told them the facts of the finances – where were we? What could we do? What would be required to save it? There was a guy at the back who was a musician who played – he played the timpani, played drums and the brutal bells that you ring from time to time. And I said, ‘You know, there’s a problem.’ And he says, ‘What’s the problem?’ He says, ‘We play the greatest music in the world, and if people don’t want to come and listen to us, that’s their fault.’

There really is a touch of that in the way I often hear higher education talk about itself.

Bob Rae’s prescription was as follows:

There’s a difference between consumer driven organizations and producer driven organizations. Universities, colleges and orchestras are classic examples of producer driven organizations. But the fact is, nobody can be a totally producer driven organization, because you’re living in the marketplace of ideas, of competition, of choices.

We do of course have to be very careful in higher education with student-as-consumer metaphors for any number of important reasons.

But it did set off a series of conversations, which for me really came down to this – strategically, what sort of relationship do universities want with students?

It’s complicated

Everywhere I look, all around the world, universities are re-evaluating their relationship with students.

Sometimes this happens through deliberate strategic reflection – but more often it’s done piecemeal, or in the teeth of a crisis. In most countries, Israel/Palestine encampments were a case study in institutions discovering, mid-emergency, that they had no shared language with students about what “partnership” meant or how disagreement should work.

What’s become clear is that the relationship neither can be what it was in the past nor be reduced to something simplistic. There’s a strong argument for “partner” when it comes to learning – students don’t “buy” a first, they need to put effort in, and the pedagogical relationship only works if both sides recognise their responsibilities.

But “consumer” starts to make more sense over facilities. If the toilet paper runs out, we don’t – or at least shouldn’t – expect students to nip to Nisa to sort it themselves. I’ve often said that students are perfectly capable of embodying different models at different times over different things, and to suggest (either implicitly or explicitly) that they can’t or won’t suggests the education the sector offers isn’t very “higher”.

The structural case for thinking about properly is compelling. When you shift slowly to students paying, they expect a stake in how that money is spent. Deference to authority is in global decline – today’s students have never lived in a world where institutions were automatically trusted. Lifelong learning means students increasingly aren’t juniors to be formed but adults engaged in continuous reskilling.

Massification makes efficiency-driven approaches feel hostile to humans, and partnership is how educators understand what that efficiency costs. And AI is collapsing the knowledge-gatekeeping model entirely, shifting value to the learning process itself, which can only improve through partnership. Metrics tell you “that” but not “why” – student voice is what interprets what data actually means. And the evidence on learning is clear – it requires agency, so you cannot demand active learning while treating students as passive recipients.

The political reasons for reform are equally urgent. Universities face a choice – own your accountability through partnership or have crude compliance imposed from outside. Widening participation has changed who students are – first-generation students don’t know the unwritten rules, and you need students to articulate them. Values education is shifting from content to conduct, making partnership itself a form of values education in action.

Fairness is becoming the dominant political and regulatory frame, and if it’s to feel fair, students must help define what fairness means and judge whether it’s being delivered. The old model of expert autonomy is being reframed everywhere as expert partnership – “doctor knows best” becoming “doctor brings clinical expertise, patient brings lived expertise.”

Academics might know the discipline – but students know what works for them. And fundamentally, if universities claim to produce graduates who can change the world through critical thinking and civic engagement, they need to ask whether they’re modelling the social relations they say they’re preparing students for – or running hierarchical institutions and hoping students learn democracy in what’s left of their “spare time”.

Doing grown-up

I’ve been talking about these things all week – and not just with the smart folk at the conference. From Sunday to Wednesday I was mooching around students’ unions, associations and federations – talking to both students and their reps, trying to understand how Canadian students organise, what they do, and how they relate to the institutions they’re part of.

From a Twix/Raider perspective, it was baffling. On the one hand, students have almost no formal role in quality assurance, are rarely positioned as partners in institutional governance, and to the extent that they do “representation”, it’s often about everything other than the education itself.

No wonder several university people at Re:University were bemoaning student “protest” over change – and no wonder a common default assumption is that their student reps can’t do grown-up or trade-offs.

Some leaders at the event had tales of doing direct consultation with students to get around their “political” SU officers. But what sort of signal does that send? “I’d like to avoid democracy and talk to the students who structurally feel more deferential to me.” Is that really the best we can do?

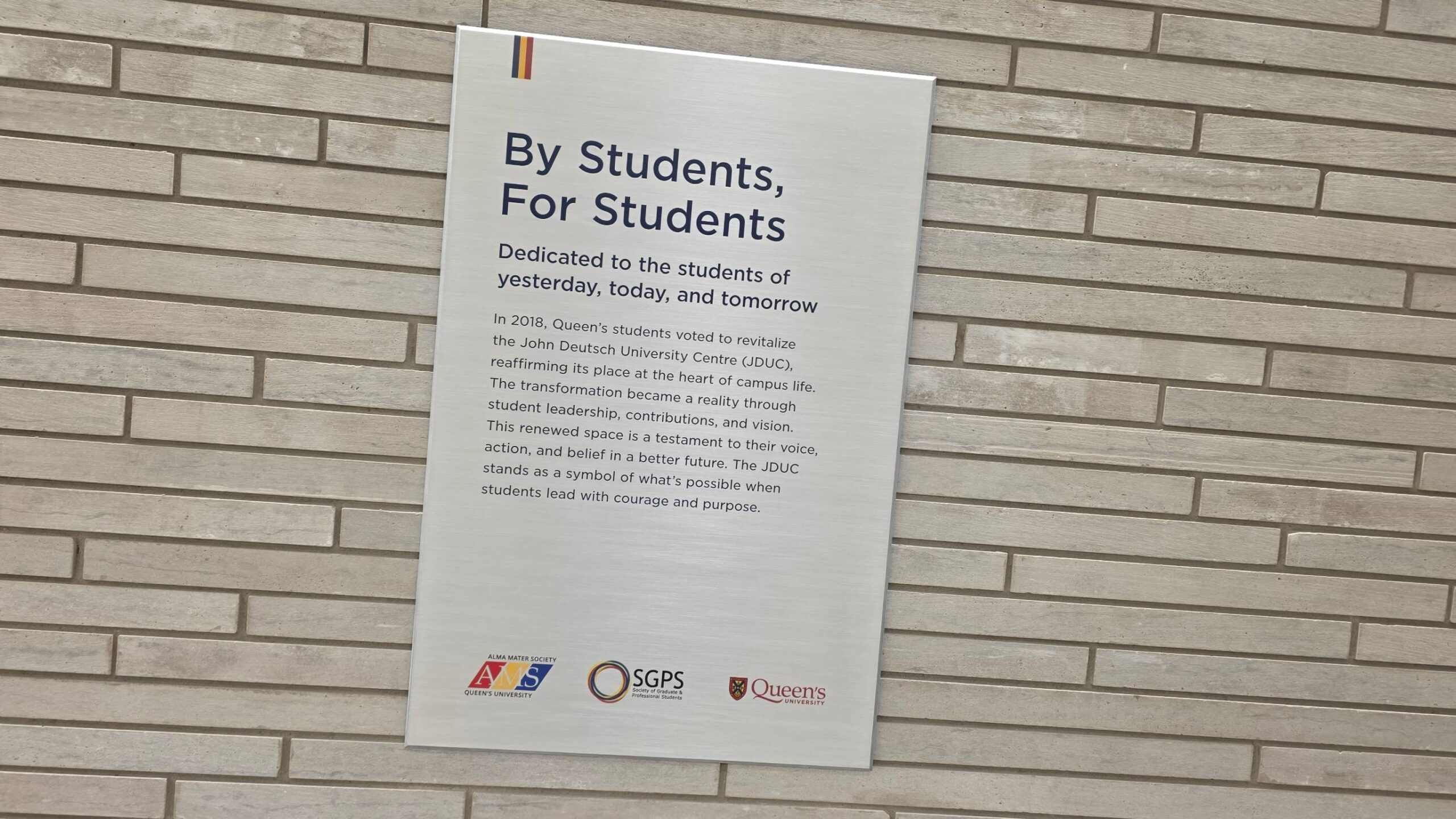

And yet – several of the SUs I visited, which unlike in the USA are still democratically run and governed, and unlike in the UK have very few career staff, control vast budgets over large chunks of student services, raising the fees for those services via referendum.

On that stuff, they’re routinely doing “grown-up” and “trade-offs” – even within an explicitly democratic structure. The problem isn’t that students can’t handle complexity. It’s that they’ve only been trusted with complexity in certain domains.

In massified, hyper-diverse student bodies who are time poor, the need to drive engagement matters even more to ensure students feel seen and heard. But that can’t be all done “through the centre” – the student body is too big.

You have to correct for the differential levels of cultural capital and confidence without descending into disadvantage characteristic being seen as the sole and defining ones. Fundamentally, you have to think meso – without slowing everything down.

The whole pyramid

As well as who engages, what they engage on should be a feature of strategy – and that’s partly a Maslow thing.

I often think about how universities in different countries have divided responsibility. Here it has felt like universities claim the apex of the hierarchy – intellectual development, learning, the degree – while treating everything below as someone else’s problem. Food bank? SU. Housing advice? SU. Mental health campaigns? SU. Belonging through clubs and societies? SU. Crisis support? The SU.

University handles the education. Students handle the student.

But to the extent to which you “buy” Maslow, there a problem. The basic psychology says you cannot self-actualise if basic needs aren’t met. Hungry students can’t learn, anxious students can’t think, students who don’t belong disengage, and unsafe housing prevents thriving.

The pyramid has a structure – you build from the bottom. And will all respect to those I’ve spent time with this week, Canada can feel like it’s built a system where universities claim only the apex while treating everything below as someone else’s responsibility.

Partnership starts there – not with committee seats or surveys, but with a fundamental question – what does education require? If learning requires the whole person, then separating “education” from “the student” is incoherent.

But it’s also a history thing. And in organisations which are much better at looking back than they are at looking forward – and where quality is often about resembling what was done or produced prior – history matters.

Who pays?

Three models are instructive. Medieval Bologna, founded around 1088, was a universitas scholarium – a corporation of students. Older professionals travelling to learn law organised themselves for mutual protection, which evolved into collective bargaining, which became institutional control. Students hired and fired professors. Students set curriculum, timetables, fees. A “Denouncers of Professors” committee monitored staff and reported misbehaviour. The Dominus Rector who ran the university was a student, elected by peers.

Paris was different – a universitas magistrorum, a corporation of masters. Younger students studying theology under Church authority. The Church paid the teachers, so the Church (via the masters) decided everything. Students were there to be formed, not to shape the institution. At Bologna, students paid, so students decided. At Paris, the Church paid, so masters decided.

Then there’s Córdoba. Argentina, 1918. Students occupied the University of Córdoba – frozen in place since its Jesuit founding in 1613 – and issued the Liminal Manifesto declaring universities “secular refuge of mediocrities.” What they won was cogobierno – co-government – a tripartite system of students, professors and alumni, with the election of rectors by assemblies of all three groups. It spread across Latin America and created an entirely indigenous tradition of student power that owes nothing to European diffusion.

It’s an oversimplified explanation, but Canada feels like Paris model filtered through British colonialism. The inheritance descends from Paris via Oxford and Cambridge – governance by professors and Senate, students as members to be educated rather than partners in the enterprise.

And crucially, there’s been no transformative moment. No Córdoba uprising demanding co-government, no Bologna Process pushing student engagement in quality assurance, and no national equivalent to QAA student reviewers or sparqs.

As Alex Usher has observed, Canada has never attempted to impose external quality assurance on established universities – which is “100 per cent the norm virtually everywhere else in the world.” Ontario’s quality council is “relatively toothless” and was “set up by universities themselves rather than government.” Universities Canada’s position is that “each Canadian university is autonomous in academic matters” and “determines its own quality assurance standards and procedures.”

The result is a system that feels steeped not in a tradition but in the absence of disruption. Students are voices to be consulted, feedback via NSSE surveys, representatives on committees – but not partners. Certainly not employers of academics, as at Bologna.

Join the party

On the long train journeys this week, you’d expect my Eurovision playlists to be in the earbuds. Canada may well be about to “join the party” – an EBU announcement on participation is expected any day. And partly because of a need to distance itself from North America, and partly because of the French thing, there’s often speculation about Canada even joining the EU.

You don’t need to join the EU to take part in Bologna – but as a thought experiment, I’ve been goading delegates with what it would require while I’ve been here.

The Bologna Process is often assumed to be about compliance – credit frameworks, qualifications frameworks, structural alignment. But beyond those mechanics, it’s about aspiration. And the student engagement aspirations are striking.

Bologna commits to structured student roles not just at institutional level but at system level. The European Standards and Guidelines were developed jointly with the European Students’ Union – students at the table when the framework was designed. Countries commit to working towards minimum participation standards, formal roles in external quality assurance, and – crucially – treating student voice as integral to quality rather than decorative.

What does that look like in practice? At the University of Tartu in Estonia, students lobbied to make module evaluation completion compulsory – not the institution imposing it, but students demanding it. The logic is that students expect detailed feedback on their work for their learning, so the deal negotiated was – to pass a module, complete feedback on teaching and on your own engagement.

Results are made public. What’s being done about problems is made public. Institute student councils use the data to track trends and identify issues. Students are doing quality assurance in real time with real data.

In Belgium, student services operate through co-determination – students and institution decide together what services exist, how they’re designed, how they’re run. Not “we do this, you do that” but “we do this together.” In Sweden, students have a legal right to be consulted on all decisions affecting them – not a bureaucratic nightmare but a backstop that corrects for asymmetry of power.

Multiple European systems give students a third or half of seats on governing bodies. Some have veto power on specific decisions. And the evidence after decades of this? The sky hasn’t fallen in. Decisions don’t take longer but they do stick better. The extra effort required on both sides to understand each other’s perspectives produces forced dialogue rather than imposed solutions.

There’s an epistemic argument here too. Hierarchies have a structural problem – good news travels up, bad news doesn’t. Everyone tells the boss what the boss wants to hear. Students with real power become a channel for information that would otherwise be filtered out. Partnership isn’t just fair – it’s useful.

HEPI’s research on the Israel/Palestine encampments is instructive. Analysis of how UK institutions navigated those protests found that senior engagement with encampments was key to dousing flames – not escalation, not calling in police, but leaders actually talking to students as people with legitimate concerns even when they disagreed with their methods.

Institutions that had practiced partnership found they had the relational infrastructure to manage crisis. Institutions that hadn’t discovered – too late – that they had no shared language for disagreement.

Not sovereignty

I had wondered whether the widespread admiration for Mark Carney’s Davos speech was a West Wing political hack novelty – had it actually had an impact domestically?

I’m not sure. It’s true that most families are mainly focused on making ends meet, and grand geopolitical repositioning feels abstract when you’re worried about the grocery bill. But there has been evidence here in Ottawa that the speech did land domestically. There’s an aspiration to link individual effort to collective endeavour – to escape the sense of drift that comes from being positioned as America’s quiet neighbour.

Three lines feel relevant:

Collective investments in resilience are cheaper than everyone building their own fortresses. Shared standards reduce fragmentation.

That’s literally the logic of Bologna. ECTS, qualifications frameworks, recognition rules, QA alignment – these are shared standards designed to prevent fragmentation. Middle powers pooling rules to preserve autonomy.

This is not sovereignty. It’s the performance of sovereignty while accepting subordination.

There’s something in that for Canadian HE. Provincial jurisdiction over education is presented as sacred autonomy, but the result is that it’s harder to move within Canada than within Europe. Credits don’t transfer predictably, student financial support penalises mobility, and recognition is case-by-case rather than systematic. That’s not sovereignty – it’s fragmentation dressed up as principle.

It means creating institutions and agreements that function as described.

That’s almost a direct description of what Bologna compliance requires. Not rhetoric about student voice, but actual mechanisms that deliver it.

So what if Canada joined the European Higher Education Area? And by proxy, what if the UK were more enthusiastic about its continued membership?

Aspirations

On student engagement specifically, Canada would need minimum participation standards across provinces – currently it varies wildly. Formal roles for students in external quality assurance – currently OUCQA is essentially universities auditing themselves with no students on panels. There’s no equivalent to QAA in Wales or Scotland, where students are “full and equal members” of review teams.

The Bologna lens suggests that Canada piecemeal espouses student voice but has no system-level mechanism to ensure it happens. For both countries, it would mean treating the fundamental values agenda – academic freedom, institutional autonomy, student participation, public responsibility – as more than rhetorical decoration.

Choice matters in the Bologna aspirations. The ability for students to credit-gather and module-gather across disciplines, getting credit for skills developed outside the classroom, and breaking the assumption that disciplines “own” all the credit and students move through predetermined pathways like products on an assembly line are all where Europe is heading.

The “social dimension” requires not just access but explicit identification of under-represented groups, measurable objectives linked to completion rather than just entry, data infrastructure that tracks students across their entire lifecycle disaggregated by background, and accountability mechanisms that link funding and quality assurance to actual delivery on equity. Unlike in England, it would be crucial to see practice through the lens of subject to really have an impact on academic culture.

In Bologna, mobility is framed as an inclusion tool – the removal of structural barriers, portability of grants and loans, guaranteed recognition within defined timelines, not the current Canadian reality where it’s harder to move between provinces than between European countries.

And crucially, learning and teaching are treated as a policy priority in their own right – programme design based on learning outcomes, periodic review focused on whether students are actually learning, not just whether institutions followed their own processes. All have talked about over the two days here.

The public responsibility commitment is perhaps the most challenging. Bologna holds that governments bear responsibility for quality, equity and recognition integrity – with intervention powers where institutional behaviour undermines public trust.

That sits uncomfortably with both Canadian provincial fragmentation, where authority is distributed so thoroughly that accountability has evaporated, and with the England’s current direction of travel, where the Office for Students has become more focused on culture wars and university budgets than on whether the regulatory framework actually protects students.

The Bologna lens asks a simple question – if an institution fails its students, who intervenes and who is accountable? In systems that have genuinely embraced the framework, that question has an answer. In Canada – and increasingly in England – everyone is responsible in theory, which means no one is responsible in practice.

Eating together

Outside of Bologna, other aspects matter too. Alex Usher made an observation during the event that stuck with me. One of the worst things to happen to universities over the past twenty-five years in his view is losing their faculty clubs and shared eating spaces – because there are now fewer places to discuss things in a non-high-stakes atmosphere.

If you force everything to be discussed at committees or the board, it’s never low-stakes – it’s positional and ceremonial. Aristotle, he reminded us, argued that communities that eat together are more cohesive. Universities have systematically dismantled the informal spaces where difficult issues could be discussed before they became crises.

There’s an AI dimension too. Universities as gatekeepers to information are dead – that function has been commoditised and democratised. “How to synthesise” and “how to write” are going the same way. But let students reimagine education and they consistently want to learn, solve problems, and create new knowledge – and they still want to do it physically.

Alex’s yoga analogy is useful. YouTube means you can watch the best yoga teachers in the world for free, from your living room, at any time. And yet people still come to yoga classes. They come for the structure, the accountability, the community, the embodied experience of doing something with other people. Universities (and the edtech firms that float around them) that think they’re selling access to content have fundamentally misunderstood what students are actually buying.

And there’s the Maslow thing again. Students are interested in all five levels of the hierarchy – physiological, safety, belonging, esteem, self-actualisation. Universities should be too. That points towards co-determination, not a current model of “we do your education and we know best, but on food relief and housing advice and mental health you do it and we have no role.” Either the whole pyramid matters for learning, in which case universities need to engage with all of it – or it doesn’t, in which case stop claiming that what happens at the apex is so special.

Dare to be braver

If some of that feels a bit scattergun, well – that’s what happens when a conference is designed to make you think rather than show you how to do. But more than that, what has made these final 2 days in Canada so inspiring has been this – it was mainly about everyone daring each other to be more ambitious about what staff and students can do together.

Some conferences in higher education amount to bringing together a profession to moan about how hard it is to be in that role – how other professions don’t understand, or how the government doesn’t understand, or how students are demanding, or how the funding doesn’t work, or how the metrics are unfair. Those conferences are comfortable. You leave feeling validated in your grievances.

This event was different. It was about daring each other to be braver – about asking what universities could become if they stopped defending what they’ve always been, and (at least for me) about imagining students (and staff) as confident, capable, creative partners – rather than consumers to be satisfied or critics to be managed.

Put another way, if the website, the strategy and the graduation speeches all say they’ll go and change the world, we should probably help build the scaffolds and culture that enable them to at least change their education. Practice makes perfect, eh.